The invention of music notation

Music notation has developed since ancient times to the standard five-line staff we know today. Though music is ephemeral and fleeting, it can be represented by notation, just as words can be preserved for future generations. The challenge, of course, is to represent sound and time, in particular, pitch and rhythm. The pitch is high and low, and relates to the physical frequency of the sound. The rhythms of the sounds are the proportional durations of the pitches within the steady beat or pulse of the music.

Guido d’Arezzo (c. 991-after 1033) was an Italian monk and Medieval music theorist. He often is credited with the invention of musical staff notation, and notation is truly an ingenious invention.

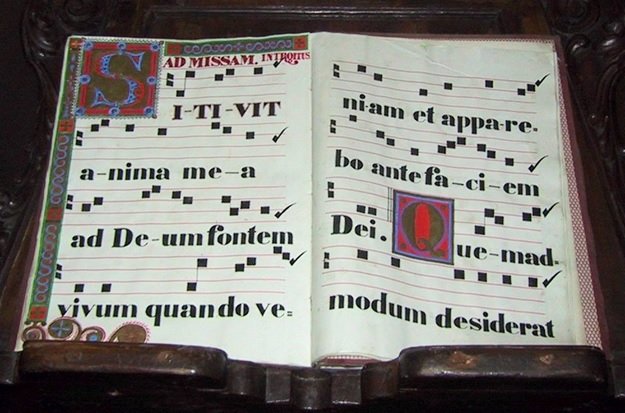

Our standard notation now probably can be traced most easily back to medieval notation, similar to that which Guido knew. Originally, notation showed the contour of the pitches without anchors or reference lines. To help singers better understand the relative pitches, a single horizontal line was introduced. It’s very precise: pitches can be on, below, or above the line. However, it’s also limited. If a tune uses more than three pitches, there is no easy way to show the fourth pitch. So, using more than one line is usually desirable, as in the example above of medieval music. The “notes” (actually called neumes) are the little black squares. If you look closely, you may be able to see that the notation uses staves with four lines each.

The staff is a kind of grid on which we locate pitches. Theoretically, we could have staves with as many lines as we like: 6, 11, or 25. Musicians gradually settled on the five-line staff as a standard for music notation because the eye seems to be able to track five lines just fine; any more and we tend to get confused.

Anyone can learn to read modern music notation. In fact, I included a complete, 16-part course, based on Khan Academy videos. It's free and available to anyone.

This blog post is taken from my book Music Theory for Choral Singers.

Next post: John Rutter on the Power of Choral Singing